As semelhanças e diferenças culturais entre o Brasil e a África Ocidental

Marco Aurelio Schaumloeffel

Depois da chegada dos navegadores portugueses ao Golfo da Guiné, na costa ocidental da África, em 1471, e ao Brasil em 1500, foi estabelecida uma ponte que ligaria culturalmente dois continentes. No Gana, antigamente chamado de Costa do Ouro, os portugueses ergueram, em 1482, na cidade de Elmina[1], o Castelo de São Jorge, a mais antiga construção européia na África sub-saariana e o primeiro de uma série de fortes e castelos erguidos por diferentes exploradores europeus, entre eles franceses, ingleses, alemães e holandeses. Dessa ocupação na África surgiu o horrendo tráfico de humanos e a exploração de bens naturais.

A maior parte dos escravos, levada como produto para o Brasil, era originária do Congo e do Oeste da África, estes genericamente denominados de “negros sudaneses”. A cadeia de negociação de humanos no mercado iniciou-se nas próprias tribos. Ao contrário do que muitas vezes se aprende nas aulas de história, o sistema de escravidão não foi introduzido pelos colonizadores europeus na África. Ele já era característica comum nas tribos ganenses antes da chegada dos portugueses. Pessoas capturadas em tribos inimigas ou contraventores das regras internas eram escravizados. Os europeus deram proporções muito maiores a esta prática, fazendo com que tribos como a dos Akan e, principalmente, a dos Ashanti, no Gana, se tornassem ricas por venderem força de trabalho aos colonizadores, que levariam negros escravizados às Índias, à Europa e às Américas. Os chefes acumulavam grandes riquezas a partir desse tipo de transação, fato que se vê espelhado ainda hoje, p. ex., na figura do rei Ashanti, que ostenta tantas e tão pesadas pulseiras de ouro a ponto de precisar de um ajudante que lhe dê sustentação aos braços no momento de cumprimentar visitantes. No Benin, até mesmo afro-brasileiros, tanto descendentes de escravos brasileiros quanto africanos libertos, atuavam como agentes escravagistas[2]. Alguns deles conseguiam juntar fortunas fabulosas com o comércio de humanos, como foi o caso de Francisco Félix de Souza, que deixou de herança uma fortuna avaliada em 120 milhões de dólares, em dinheiro de hoje.

Os escravos originários da África Ocidental, principalmente das regiões da Costa do Ouro e da Costa dos Escravos (atualmente Benin), são os que formaram, em grande parte, as populações negras da Bahia, do Maranhão e de Pernambuco. Sem poder de decisão, o negro foi arrancado de seu continente natal e inserido na sociedade brasileira; trouxe consigo sua força de trabalho, seus hábitos, seu modo de ser, sua crença, ampliando, enriquecendo e modificando, dessa forma, a cultura e o dia-a-dia no Novo Mundo. A extensão dessa contribuição é ampla, muitas vezes pouco clara para quem está inserido em seu raio de ação, ainda mais que houve, no Brasil, o encontro das culturas ameríndia, africana e européia, resultando em processos novos, porém não uniformes, o que mostra a diversidade e a impossiblidade de se descrever “a cultura” do nosso país como algo homogêneo. Viver no continente africano deixa isso muito mais exposto e faz perceber que há influências culturais de dimensões e direções variadas. Tanto a sociedade brasileira quanto as da África Ocidental sofreram transformações a partir desta ponte criada pelo tráfico estabelecido inicialmente pelos portugueses. Aqui daremos enfoque específico sobre aspectos tópicos das influências, semelhanças e diferenças existentes entre Brasil e Gana.

As artes culinárias revelam coisas interessantes sobre a cultura de um povo. Há um jogo de palavras em alemão que resume isto: “man ist was man isst” (somos o que comemos). É muito comum ver pessoas preparando pratos feitos com mandioca (macaxeira) nas ruas de Gana. A mandioca, originária das Américas, possivelmente levada à África pelos colonizadores portugueses e também por libertos que decidiram retornar ao continente natal. Ela serve de base para o famoso fufu, preparado em um pilão junto com banana-da-terra, para pirões e para a farofa, adicionada a muitos pratos, inclusive a feijão cozido que requer, assim como grande parte dos pratos, uma boa dose de pimenta malagueta. Além da mandioca, também o inhame e o milho, este também originário das Américas, são usados para fazer purês no pilão, sempre acompanhados no prato de molhos variados feitos com ingredientes como carne de porco, de bode, sardinhas, peixes secos, quiabo, cebola, pimenta e óleo de dendê. Normalmente as refeições não são feitas com talheres, mas sim, e exclusivamente, com a mão direita, pois a esquerda é considerada a mão suja. Ela também não pode ser usada para cumprimentos nem para dar ou receber presentes, o que seria uma demostração de pouca polidez. Nas ruas as pessoas montam banquinhas onde preparam lanches rápidos, entre eles amendoins torrados, castanhas de caju, bolinhos, bananas e carnes fritos em óleo de dendê. As laranjas, assim como em várias partes do Brasil, são oferecidas já descascadas ao lado de pedaços de manga, mamão, abacaxi ou pedaços de cana-de-açúcar prontos para serem mascados. Para a sede pede-se uma água de côco. Quase todas as mulheres, que formam o pilar-mestre do comércio ganense, carregam suas “lojas” em grandes bacias sobre a cabeça em um equilíbrio inacreditavelmente perfeito. É impressionante observar a dança e a sincronia de um mercado repleto de mulheres carregando objetos de toda ordem, pesos e tamanhos por sobre a cabeça. Delas é possível comprar desde esmalte para unhas até frutas, verduras, ovos e calças masculinas. Essas semelhanças na comercialização, na plantação e no consumo de alimentos exibe um dado curioso: enquanto o Gana é o segundo maior produtor de cacau do mundo (a vizinha Costa do Marfim é o primeiro), originário das Américas, nós somos o maior produtor de café, originário da África. No Benin, como descreve Guran (2000: 123-124), há, inclusive, entre outros, “feijoadá”, “moukeka” e o “kousidou”, além de sobremesas como a “concada”, levados para lá pelos agudás, os assim chamados retornados “brasileiros” daquela região.

Na África, as origens da música estão intimamente ligadas à religião. Da mesma forma ocorre no Brasil, onde os rituais das religiões afro-brasileiras também são acompanhados de música, tendo diferentes denominações, conforme a região de ocorrência: tambor de mina no Maranhão, xangô do Rio Grande do Norte ao Sergipe, batuque no Rio Grande do Sul e candomblé em outros estados como a Bahia e o Rio de Janeiro. Na música, muitas de nossas manifestações como samba, gafiera, choro, pagode, maxixe, maracatu, forró, frevo, embolada, côco, lundu, congadas etc. têm claras influências africanas, principalmente na percussão e nos ritmos. Alguns intrumentos de percussão foram trazidos da África, outros criados aqui por afro-brasileiros. Cuícas, ganzás, atabaques e marimbas são testemunhas dessa contribuição à música brasileira. As variações poliritmicas e as cadências africanas, unidas à melodia européia e à herança musical indígena, criaram um resultado inesperado e novo: a música e as danças brasileiras. Além disso, o carnaval, de origem européia, africanizou-se no Brasil, transformando-se na maior e mais alegre festal nacional. Além de sermos venerados por especialistas do mundo todo pela música que criamos, usamos a música para venerar, um legado tanto africano quanto indígena. Essa veneração exibe, hoje, graus diversos, desde o culto terreno ao culto do corpo de uma bela mulher até à evocação de entidades superiores abstratas.

Pensar em cultos religiosos no Brasil sem a presença de elementos africanos é praticamente impossível. Nas práticas católicas menos ortodoxas entram elementos de fetichismo e superstição; nas diferentes religões afro-brasileiras, assim denominadas por invocarem e praticarem ritos que não são puramente de origem africana, há elementos de origem indígena e européia. Para tal, basta observarmos ritos religiosos como a lavagem do Senhor do Bonfim[3] na Bahia ou as atitudes de um jogador antes do início de uma partida de futebol. As religiões afro-brasileiras sofreram influências umas das outras, de forma que há, na maioria delas, características nagô (ou iorubá, da atual Nigéria), ewe (do Togo e do oeste de Gana, muitas vezes também chamado de jejê) e bantu (do sul da África). Como o catolicismo era, durante mais de três séculos, a religião oficial e a única a ser aceita pelo Estado, a criatividade e o desejo de preservar as raízes culturais dos afro-brasileiros, já amalgamadas também por diferentes processos, colocou roupagens de santos católicos nas divindades (orixás) africanas, fazendo surgir uma curiosa duplicidade de nomes para a mesma entidade: Xangô também é conhecido por São Jerônimo, enquanto Iansã é Santa Bárbara, só para citar dois exemplos. Embora qualquer semelhança possa ser apenas uma mera coincidência, os cidadãos ganenses hoje geralmente têm dois nomes, um chamado por eles de “natural name” e outro de “Christian name”. Assim, p.ex., uma estudante de Português na Universidade de Gana, chamada oficialmente de Ekuba Dazie, também se apresenta como Patricia, dependendo da situação e de quem são seus interlocutores. Nos passaportes, a fim de evitar transtornos pessoais, as autoridades colocam ambos, o nome oficial e o cristão, normalmente criado pela fantasia de cada um. Já no Brasil, a criação da duplicidade de nomes de entidades religiosas serviu como forma de proteger e dar continuidade ao culto dos afro-brasileiros. Ela é prosaicamente chamada de sincretismo, termo divulgado e usado para explicar a suposta mistura entre os santos do catolicismo e das religiões afro-brasileiras. Há sincretismo nas religiões afro-brasileiras, mas não neste caso. Em sua verdadeira acepção, o sincretismo prevê um amálgama de concepções hetorogêneas, o que de fato aconteceu nas religiões afro-brasileiras, em processos de sincretismo interafricanos e quando estas incorporaram elementos das culturas dos povos indígenas e dos europeus. As religiões tribais na África, que hoje estão em contato permanente com doutrinas cristãs das mais variadas, parecem não ter passado por tantos processos sincréticos quanto as religiões afro-brasileiras. Lá também há pessoas que praticam ritos religiosos distintos, o que não significa que, necessariamente, haja um amalgamento entre crenças, fazendo surgir um novo produto. Da mesma forma, no Brasil, também não houve fusão entre oxirás e santos do catolicismo, como comumente divulgado; houve apenas um acobertamento das divindades africanas, forma criativa achada pelos afro-brasileiros para poder dar continuidade à prática de suas crenças, já que estas estavam proibidas pelas autoridades que só reconheciam o catolicismo como religião do Estado brasileiro.

No Gana há, atualmente, a presença maciça de igrejas cristãs. Há, inclusive, duas igrejas evangélicas vindas do Brasil. Mais de 60% da população freqüenta os cultos cristãos, embora também haja, assim como no Brasil, pessoas adeptas tanto do cristianismo quanto das religiões por eles chamadas de “naturais”. Em torno de 13% dos ganenses praticam o islamismo. Ao mesmo tempo em que as igrejas cristãs trazem consigo algumas soluções para Gana, servindo de principal atividade de encontro social durante todo o dia de domingo, causam problemas de imensurável dimensão, tentando modificar totalmente o modo de pensar e agir dos ganenses, fazendo com que, em conseqüência, toda uma postura cultural, julgada sumariamente como ruim pelos colonizadores religiosos, seja perdida. Algumas igrejas, inclusive, servem de base para acorbertar atividades ilegais ou de fonte de renda para os benefícios pessoais de pastores, que circulam em carrões novos em meio à pobreza extrema, explorando e iludindo pessoas menos esclarecidas. Um inconsciente coletivo criado por esta presença de doutrinas religiosas alheias às crenças originalmente africanas parece criar a falsa idéia de que tornar-se cristão possa ser o contraste necessário, a redenção de todos os problemas sociais e financeiros, uma vez que sociedades consideradas evoluidas – assim um esclarecido professor universitário ganense tentou certo dia me explicar – não praticam religiões que têm como deuses orixás que se originaram, p. ex., de fenômenos naturais como o raio ou do sol.

As artes africanas, assim como muitas outras manifestações culturais, têm sua motivação primodial nas religiões. As esculturas de madeiras e diferentes tipos de máscaras servem para invocar e incorporar entidades superiores ou para solucionar problemas tópicos, como é o caso da boneca de madeira akuaba que ainda hoje é usada, amarrada nas costas das mulheres ganenses, simbolizando a fertilidade e, quando grávidas, para procriar filhos inteligentes e fortes. Tanto no Brasil quanto nos países do Golfo da Guiné esta tradição da escultura permanece. Observar Ibejis, o orixá jejê-nagô, no museu Afro-Brasileiro de Salvador[4], deixa isto muito claro. Lado-a-lado estão Ibejis, muito semelhantes, procedentes de Ifahin, no Benin, e da Bahia. Hoje o talento de trabalhar a madeira é usado como meio de subsistência dos dois lados do Atlântico, até mesmo trivializando, de certo modo, o trabalho artístico. Isto é consequência natural da presença de turistas, muitas vezes pouco interessados na real cultura e que somente em busca de experiências e coisas exóticas que poderão ser mostradas a amigos na sala de casa depois da volta ao mundo chamado ocidental e civilizado.

Mais de 60 línguas[5] africanas são faladas no Gana, várias delas parecidas, embora com variações gramaticais, lexicais, sintáticas e fonéticas. A língua é o depositário da identidade cultural de um grupo de pessoas, e no Gana elas seguem o conceito tribal: cada tribo tem sua identidade comunicativa, sua língua. Os principais grupos de línguas são o Ewe, o Ga, o Fanti, o Akan e o Twi, uma espécie de língua franca falada pela maioria dos ganenses. Além desse amplo aparato lingüístico, ainda há o Inglês, única língua oficial do país, herança dos colonizadores. O inglês, menos falado que o Twi, é a principal língua usada nos meios de comunicação e normalmente é falado por aqueles que tiveram acesso à educação formal oferecida pelo estado. Foi uma surpresa encontrar, dentro deste contexto linguístico fascinante e complexo, influências da Língua Portuguesa. Uma análise cuidadosa dirime esta surpresa, uma vez que os portugueses foram os primeiros europeus a ancorar na Costa do Ouro há mais de cinco séculos; além disso, houve, há menos de dois séculos, o fenômeno de retorno de libertos e escravos revoltosos expulsos do Brasil que tinham como língua principal o Português[6]. Este legado inevitavelmente também deixou suas marcas nas línguas utilizadas pelos ganenses. Nas ruas, pedintes solicitam esmolas em inglês com a expressão “dash me something, please”. “To dash” em inglês não é sinônimo de “to give”, significa “precipitar-se, arremessar, destruir”. Uma pesquisa mais cuidadosa revelou que “dash me” nada mais é que uma interferência do Português: “dás-me”. Da mesma maneira, houve numerosas interferências do Português nas línguas africanas faladas em Gana[7]. Em Ewe fala-se “abolo” e “sabola” para “bolo” e “cebola”; em Ga é possível ouvir “ayo” e “agúia” para “alho” e “agulha[8]”; já em Akan “prékoo” e “obra” significam “prego” e “obra”, enquanto que em Fanti “komidzi” e “tabu” equivalem às palavras “comida” e “tábua”. Há, ainda, fenômenos interessantes como a palavra Fanti “faka” que significa “garfo”, provavelmente fruto de uma confusão na hora da “apresentação” de objetos novos trazidos pelos portugueses ao continente africano.

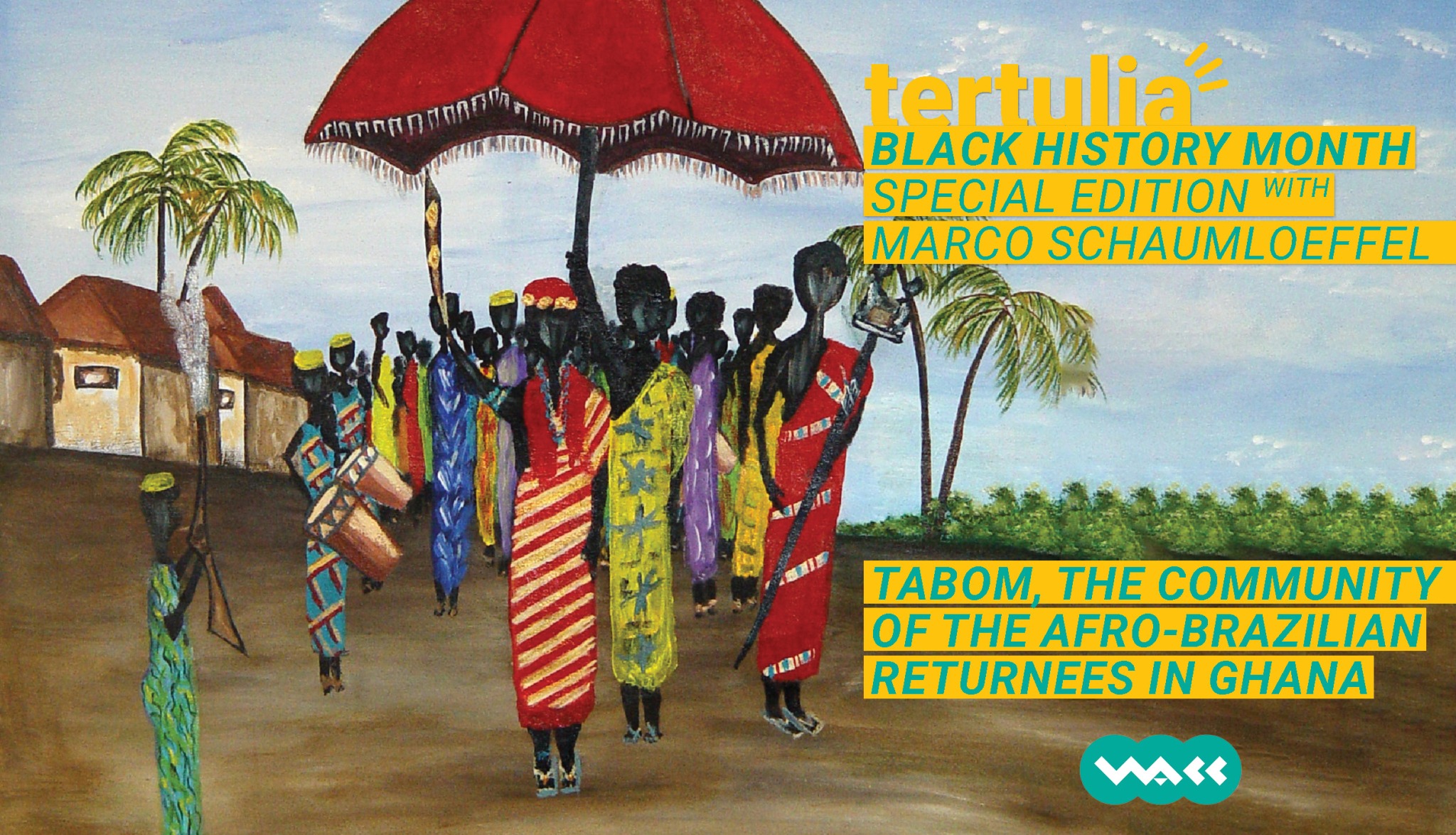

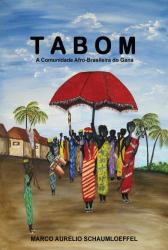

Assim como é surpreendente ouvir um “dash me” nas ruas de Acra, também não é menos interessante ouvir relatos sobre a existência de uma tribo chamada Tabom, completamente integrada ao dia-a-dia da capital ganense e parte integrante da tribo dos Ga, dominante na área. Os Tabom são libertos e expulsos pela Revolta do Malês de 1835 do Brasil que retornaram à África e acharam sua acolhida definitiva em 1836 entre a tribo Ga na então cidadezinha de Acra. Os Tabom, na sua chegada a Gana, somente sabiam falar português, usavam os cumprimentos conhecidos “Como está?” e a resposta “Tá bom”, daí provavelmente a origem do nome “Tabom people” dado a eles pelo povo Ga. Eles tinham várias habilidades, foram muito bem recebidos pelo rei Ga e ganharam terras com localizações privilegiadas; nestas terras iniciaram plantações, inclusive com sistemas de irrigação, trazendo novas técnicas aprendidas no Brasil e melhorando, dessa forma, as condições econômicas e a vida de todos. Muitos também tinham especialidades prezadas e pouco dominadas na época pelos Ga: eram carpinteiros, alfaites, ferreiros, construtores, arquitetos etc que ajudaram no desenvolvimento comercial e na melhoria das condições sanitárias do país. A contribuição dos Tabom é muito mais extensa do que as melhorias estruturais por eles promovida. Como muitos em seu retorno eram islâmicos, eles ajudaram a consolidar o islamismo na capital, no sul do país, pois o islamismo era forte somente no norte; outros Tabom levaram de volta ao seu continente uma estátua de um xangô, ainda hoje preservada e guardada sob certo mistério e cuidados. Além disso, termos do português trazidos por eles foram incorporados às línguas locais, embora ele não seja mais falado atualmente. A culinária, a música, a dança e o jeito de vestir sofreram uma “re-influência”, refazendo o caminho cultural África-Brasil-África. Apenas a título de exemplo, é possível observar, em uma das fotos antigas dos Tabom, o chefe Tabom, de traços físicos semelhantes aos chefes Ga com quem está reunido, de terno preto e gravata, enquanto que seus colegas, na reunião de chefes com o rei, estão todos vestidos com túnicas longas e coloridas, bem à moda ganense.

Apesar de todas estas semelhanças, viver o dia-a-dia em um país como Gana também expõe muitas diferenças. A percepção do corpo é diferente da nossa; há muito espaço para vaidades, mas ainda não há a preocupação extrema em seguir e ser como modelos impostos pela cultura e pela mídia ocidental. Há modas, mas nada que faça todos parecerem ter as mesmas preferências. É interessante para mim, depois de um ano, voltar de férias para o Brasil em 2004 e ver que em Curitiba, cidade onde vivi oito anos antes de ir para a África, a imensa maioria das mulheres nas ruas com, pelo menos, uma peça de roupa cor-de-rosa. Há casos extremos de moças com combinações desde a sola dos sapatos, calças, cinto, blusinha, roupa íntima à mostra, faixa de cabelo e telefone celular nas mais diferentes tonalidades da cor rosa. Este tipo de fenômeno, principalmente gerado pelas mídias de massa, que transforma cada indivíduo em apenas um componente de uma massa homogênea, ainda não há em Gana. Lá as mulheres, por questões culturais e religiosas, não expõem tanto o corpo, não mostram jamais o umbigo, tão fácil de ser visto mesmo no inverno do Sul do Brasil. Nas praias, o traje feminino de banho e passeio é um vestido longo, enquanto que para os homens um calção ou mesmo a nudez são tolerados. Por outro lado, na cultura rural, na vida tribal, não há o menor problema para as mulheres em andar com os seios de fora. As necessidades fisiológicas, mesmo nas maiores avenidas da capital, têm prioridade. Urinar ou defecar, seja de frente para uma rua movimentada, em uma ponte ou na areia da praia, não exige nenhum pudor, afinal é apenas visto nessa cultura como necessidade comparável a respirar.

Outra grande diferença cultural está no modo de realizar os ritos de funerais. Em Gana faz-se festejos de funeral. A morte de alguém da família significa tristeza apenas no momento inicial e somente para os familiares mais próximos, normalmente os que conviviam com o falecido. Passado isto, a família deve ser reunida para planejar a festa de funeral, que acontecerá três ou quatro semanas mais tarde, em um final de semana, de sexta a domingo, quando todos tiverem a possibilidade de estar presentes. Durante este período, o cadáver fica em geladeiras apropriadas para sua conservação, enquanto que é feita a encomenda, para aqueles que seguem as religiões naturais, do caixão personalizado. Estes caixões são de tamanhos e formatos diferentes e alegres, pouco semelhantes com aqueles padronizados e lúgubres que temos. Se o falecido foi pescador, o caixão terá formato de sardinha gigante ou de réplica de seu barco de trabalho; um caçador valente terá um caixão imitando um leão, um pastor uma bíblia, um adorador de carros alemães um caixão estilo BMW ou Mercedes e o apreciador de cerveja será enterrado dentro de urna funerária em formato de garrafa enorme decorada com a marca preferida. No final de semana da festa, normalmente enterra-se o cadáver na sexta-feira. Logo em seguida começa a festa que durará até domingo à noite. Dependendo do poder aquisitivo da família, contrata-se uma banda, vários tipos de comida são preparados, tudo regado a chope, vinho, champanha, destilados e refrigerantes. Todas as pessoas que estiverem a fim de participar da festa podem comparecer, mas geralmente só há a “obrigação” de não deixar faltar nada aos convidados oficiais. Há casos de famílias que contraem grandes dívidas por causa da morte de um familiar; as festas de funeral exigem esforço colossal de todos os parentes próximos. Durante as três semanas de preparação as crianças deixam de ir à escola e os adultos não comparecem ao trabalho, o que é aceito culturalmente sem restrições. O falecimento é um evento social, que envolve danças, bebidas alcoólicas, alegria, uma forma de reencontrar parentes e amigos, uma oportunidade, p.ex., de jovens conhecerem pretendentes, tendo, só que em caráter mais amplo, a mesma função social que as igrejas desempenham aos domingos. A idéia primordial da festa de funeral era despedir alegremente a alma desta vida, para que ela pudesse ir em paz para encontrar, em outro mundo, seus antepassados de forma comemorativa, sem tristezas. Além disso, ela também tinha a função de acolher e alimentar pessoas que vinham de longe, de outras aldeias, após horas ou dias de caminhada.

Uma das mais interessantes vitrines de interpretação da cultura de um povo são as propagandas. Enquanto nós achamos muito normal associar o formato de uma garrafa ou o gosto de uma cerveja a mulheres belas, em Gana surte efeito o que pode ser chamado de “realismo fantástico”. Remédio que cura diarréias deve ter uma placa na rua com a ilustração de uma criança de cócoras sofrendo as conseqüências da disenteria; remédio contra impotência logicamente mostra o desenho de um homem grande e forte tendo uma ereção, ao contrário da nossa linguagem que prefere propagandas com jogos de palavras que permitam interpretações cheias de segundas intenções; um médico que trata hérnias coloca em frente ao consultório ilustrações com anomalias desproporcionalmente grandes nas mais diferentes partes do corpo; para mostrar a resistência de um reservatório de água na TV, monta-se uma cena de um acidente de caminhão, na qual o tanque transportado cai e desce rolando um morro enorme e não estraga. Estes são apenas alguns exemplos de propagandas efetivas em Gana que causariam estranhamento cultural e poucos resultados positivos para o anunciante, caso fossem usadas em nosso meio.

O papel de mulheres e homens na sociedade é muito diferente. As mulheres são vistas como as provedoras de filhos e, na maioria das vezes, também dos alimentos para a família. Em grande parte das tribos ganenses, mesmo nas de perfil urbano, o sistema de organização familiar é matriarcal. A mulher é chefe da família, coordena o dia-a-dia econômico e social e tem os direitos sobre a herança. Segundo relatos de vários ganenses, esse sistema é o mais fácil, pois todos têm certeza de quem é sua mãe, o que nem sempre acontece em relação ao pai, já que a poligamia, embora indesejada pelas mulheres, é tolerada por todos. Apesar de todo o trabalho doméstico, as mulheres também são responsáveis pela maior parte da entrada de recursos na família. Elas vão à feira vender o que produziram no quintal de casa ou foram colher na natureza. É comum ver mulheres carregando seus filhos amarrados às costas e uma grande e pesada bacia de produtos para vender na cabeça, acompanhada de seu marido, que caminha tranqüilamente de mãos vazias à frente dela.

Estar em um país com 99,8% de negros e ser branco impõe uma situação extremamente interessante, do outro lado da moeda, fazendo sentir e entender muitas das situações pelas quais passam negros no Brasil, embora estes estejam longe de ser uma minoria. Geralmente minorias são discriminadas de alguma forma, pelo simples fato de serem diferentes do “padrão”, sejam elas de qualquer origem. Em Gana, quando avistado um branco, é muito comum as pessoas berrarem por todos os cantos e em qualquer situação “hello oburoni”, o que significa “olá homem branco”. Comportamento deste tipo com, p.ex., afro-brasileiros ou descendentes de japoneses não seria tolerado nas ruas do Brasil. Segundo os ganenses, é apenas uma forma de bem receber estrangeiros, mesmo que oburonis não se sintam tão à vontade com a rotulação pública. Há várias implicações embutidades nesta atitude relativamente ingênua, que resultam, obviamente, em tratamento desigual.

Haveria a possibilidade de discorrer longamente sobre este e outros temas, mas a intenção deste artigo é de apenas fazer o registro de algumas impressões de vivências pessoais, mostrando muitas semelhanças e alguns contrastes que há entre as várias atitudes culturais brasileiras e as do Golfo da Guiné. Desse modo, esperamos ter contribuído, nem que minimamente, para que criemos consciência e valorizemos nossas raízes, os componentes formadores de um Brasil heterogêneo, múltiplo, sejam eles originários da África, da Europa, da Ásia ou das Américas. A ponte criada entre o Brasil e a África, embora seja fundamental, basilar para nossa cultura, muitas vezes é estranhamente por nós ignorada. O que sabemos nós da África? O que queremos saber? Quem renega suas origens renega a si mesmo.

Bibliografia

AKROFI, C. A. et allii. An English-Akan-Ewe-Ga dictionary. Accra : Waterville Publishing House, 1996.

BARATA, Mário et allii. The African contribution to Brazil. Rio de Janeiro : Edigraf, 1966.

GURAN, Milton. Agudás : os “brasileiros” do Benin. Rio de Janeiro : Nova Fronteira, 2000.

LANGUAGE GUIDE. Akuapem-Twi Version. 3. ed. Bureau of Ghana Languages, Accra, 2000.

LANGUAGE GUIDE. Fante Version. 7. ed. Bureau of Ghana Languages, Accra, 1990.

RODRIGUES, Nina. Os africanos no Brasil. 4. ed. São Paulo : Editora Nacional, 1976.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. African influence in Brazil. Daily Graphic. Accra, v. 149.122, p. 7, 2004.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. Tabom: The Afro-Brazilian community in Accra. Daily Graphic. Accra, v. 149.143, p. 14, 2004.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. The African influence on Brazilian music. Daily Graphic. Accra, v. 149.132, p. 14, 2004.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. The Afro-Brazilian religions. Daily Graphic. Accra, v.14915, p. 9, 2004.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. The influence of the Portuguese Language in Ghana. Daily Graphic. Accra, v. 149.120, p. 7, 2004.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. The links between West Africa and Brazil in the Culinary Art. Daily Graphic. Accra, v.149137, p. 14, 2004.

VALENTE, Waldemar. Sincretismo religioso afro-brasileiro. 2. ed. São Paulo : Companhia Editora Nacional, 1976.

VERGER, Pierre. Fluxo e refluxo do tráfico de escravos entre o Golfo do Benin e a Bahia de Todos os Santos : dos Séculos XVII a XIX. São Paulo : Corrupio, 1987.

Notas:

[1] Do português „A Mina“, em referências às várias minas de ouro da região.

[2] Estes fatos são muito bem documentados e descritos tanto por Verger quanto por Guran (ver bibliografia).

[3] A festa de N. S. Do Bonfim é, aliás, também festejada, ao lado da festa da burrinha (chamada de “bourian”) pelos “brasileiros” do Benin, como descreve o fotógrafo e antropólogo Milton Guran (2000: 126-168).

[4] Este museu é muito interessante, mas, apesar de ser bastante freqüentado por um grande número de turistas estrangeiros, infelizmente não apresenta explicações escritas ou orais em outras línguas, apenas no Português do Brasil.

[5] Ao invés de „línguas“ o termo „dialetos africanos” é comumente mais utilizado, embora estes “sistemas de comunicação” apresentem variações gramaticais, lexicais, sintáticas e fonéticas.

[6] Sobre o fenômeno dos afro-brasileiros que retornaram à África discorrerei mais adiante.

[7] Aqui serão apresentados somente alguns exemplos. O fenômeno da interferência do Português no Inglês e nas línguas africanas falados em Gana é bem mais amplo.

[8] Termo somente para utilizado para a agulha usada na confecção de redes de pescar.

Os Tabons do Gana, a diáspora afro-brasileira na África Ocidental ainda pouco conhecida

Os Tabons do Gana, a diáspora afro-brasileira na África Ocidental ainda pouco conhecida

Texto selecionado no I Concurso Literário de Poemas e Contos em Hunsrückisch e publicado no livro “Hunsrückisch em Prosa e Verso”, páginas 93-96.

Texto selecionado no I Concurso Literário de Poemas e Contos em Hunsrückisch e publicado no livro “Hunsrückisch em Prosa e Verso”, páginas 93-96.

Entrevista concedida à revista Atlântico / Interview for Atlantico Magazine

Entrevista concedida à revista Atlântico / Interview for Atlantico Magazine

O primeiro livro sobre a história dos tabons, a comunidade afro-brasileira do Gana. Eles voltaram à África Ocidental entre 1829 e 1836. “Este livro parece pequeno, mas possui muitas portas, como se fosse um casarão. Elas se abrem para várias e diferentes paisagens e nos deixam ver, primeiro, de fraque e cartola e, depois, envoltas em belo pano kente, as figuras humanas que as povoaram e cujas histórias os atuais tabons repetem de cor. Se, em suas páginas, aprendemos muito sobre o grupo tabom, graças ao cuidado e à inteligência com que Marco Aurelio Schaumloeffel soube ouvir e ler, elas nos pedem que saibamos mais.” (Alberto da Costa e Silva).

O primeiro livro sobre a história dos tabons, a comunidade afro-brasileira do Gana. Eles voltaram à África Ocidental entre 1829 e 1836. “Este livro parece pequeno, mas possui muitas portas, como se fosse um casarão. Elas se abrem para várias e diferentes paisagens e nos deixam ver, primeiro, de fraque e cartola e, depois, envoltas em belo pano kente, as figuras humanas que as povoaram e cujas histórias os atuais tabons repetem de cor. Se, em suas páginas, aprendemos muito sobre o grupo tabom, graças ao cuidado e à inteligência com que Marco Aurelio Schaumloeffel soube ouvir e ler, elas nos pedem que saibamos mais.” (Alberto da Costa e Silva).

The first book on the History of the Tabom, the community of the Afro-Brazilian returnees in Ghana. They returned to Ghana from Bahia between 1829 – 1836. “This book seems to be small, but has many doors, as if it were a mansion. They lead to several and different sceneries and let us see, first, in tail-coat and top-hat, and later wrapped in a beautiful kenté cloth, the human beings who filled them and whose stories the Tabom of today repeat by heart. If in its pages we learnt a lot about the Tabom People, thanks to the accuracy and the intelligence with which Marco A. Schaumloeffel listened and read, they demand from us, that we learn more.” (Alberto da Costa e Silva).

The first book on the History of the Tabom, the community of the Afro-Brazilian returnees in Ghana. They returned to Ghana from Bahia between 1829 – 1836. “This book seems to be small, but has many doors, as if it were a mansion. They lead to several and different sceneries and let us see, first, in tail-coat and top-hat, and later wrapped in a beautiful kenté cloth, the human beings who filled them and whose stories the Tabom of today repeat by heart. If in its pages we learnt a lot about the Tabom People, thanks to the accuracy and the intelligence with which Marco A. Schaumloeffel listened and read, they demand from us, that we learn more.” (Alberto da Costa e Silva).

Este livro descreve e analisa o estado atual do dialeto Hunsrück de Boa Vista do Herval (DBVH), uma pequena comunidade no RS, Brasil (20km de Gramado). Os dados apresentados baseiam-se em transcrições de quase 20 horas de gravações com 36 falantes, selecionados segundo critérios sociolingüísticos. O ponto central é a análise das interferências do português no DBVH, tanto no âmbito gramatical (gênero, verbos, formação de plural etc.) quanto no lexical-semântico (palavras de várias áreas: família, cozinha, profissões, tecnologia etc.).

Este livro descreve e analisa o estado atual do dialeto Hunsrück de Boa Vista do Herval (DBVH), uma pequena comunidade no RS, Brasil (20km de Gramado). Os dados apresentados baseiam-se em transcrições de quase 20 horas de gravações com 36 falantes, selecionados segundo critérios sociolingüísticos. O ponto central é a análise das interferências do português no DBVH, tanto no âmbito gramatical (gênero, verbos, formação de plural etc.) quanto no lexical-semântico (palavras de várias áreas: família, cozinha, profissões, tecnologia etc.).