Artigo publicado

Por que dizer “sich aposentieren” no Hunsrückisch brasileiro está correto?

Revista Projekt, número 52, Dezembro de 2014 – ISSN 1517-9281

Artigo em pdf

Revista completa

Por que dizer “sich aposentieren” no Hunsrückisch brasileiro está correto?

Marco Aurelio Schaumloeffel, University of the West Indies, Barbados

Introdução

Você acharia graça se alguém usasse a palavra Fenster em Hochdeutsch (alemão-padrão) ou a palavra armazém em português? Provavelmente não, por considerá-las palavras que fazem parte do léxico, do vocabulário “normal” destas línguas. Contudo muitos acham graça e até mesmo consideram erro crasso alguém usar palavras provenientes do português nas variantes dos dialetos Hunsrückisch[1] falados no Brasil. Taxam o Hunsrückisch de “alemão-de-capoeira”, “língua de colono pobre e coitado”, “coisa de ignorante”, “língua de gente que não sabe falar direito”, “alemão errado”, para me restringir a apenas alguns dos termos que já ouvi pessoalmente.

O objetivo deste curto artigo é esclarecer, desmistificar e explicar de forma simples os motivos pelos quais palavras do português são emprestadas, incorporadas e usadas na língua que muitos falam como sua língua materna, especialmente no sul do Brasil.

O Empréstimo Linguístico

As afirmações acima sobre o Hunsrückisch brasileiro não passam de preconceito linguístico, devido ao status social a ele conferido ao longo dos anos. O preconceito linguístico é “mais precisamente o julgamento depreciativo, desrespeitoso, jocoso e, consequentemente, humilhante da fala do outro (embora preconceito sobre a própria fala também exista)” (Scherre 2008, p.12). Estas afirmações acerca do Hunsrückisch brasileiro não possuem, contudo, nenhuma base lógica ou correta do ponto de vista científico dos estudos em Linguística. Cabe aos estudiosos das línguas a análise e a contextualização de fenômenos que ocorrem dentro dos mais diversos aspectos da gramática e do vocabulário. Para que entendamos melhor o fenômeno do uso de palavras do português no Hunsrückisch brasileiro, gostaria de brevemente mencionar a origem das duas palavras mencionadas acima como desencadeadoras dessa reflexão: Fenster e armazém, presentes no alemão e no português atuais, respectivamente.

Essas palavras são aparentemente triviais e fazem parte inquestionável de sua respectiva língua, mas, historicamente, elas também são fruto de empréstimos linguísticos[2]. Em termos simples e sem entrar em nuances e detalhes de como ocorre esse fenômeno, um empréstimo linguístico é a transferência, o empréstimo de um termo de uma língua para outra. Há vários motivos pelos quais empréstimos linguísticos são feitos, mas de forma generalizada podemos afirmar que eles ocorrem principalmente porque um determinado termo não existia no momento de sua incorporação na nova língua ou porque o novo vocábulo viria substituir um termo anterior, o qual talvez tenha caído em desuso ou que, p. ex., possa ter perdido seu status de uso no dia-a-dia. Há, ainda, casos de empréstimos que são incorporados com a finalidade de desambiguação. No português atual, p.ex., a palavra inglesa off parece ter um status maior, ao menos nos shoppings, do que a palavra desconto, embora muitos talvez nem saibam exatamente o que off signifique.

Voltemos, contudo, aos exemplos mencionados acima. A palavra alemã Fenster deve sua origem ao latim; após algumas transformações linguísticas bastante comuns (alterações fonéticas e morfológicas), o termo latino fenestra (janela) transformou-se em Fenster. No português temos a palavra defenestrar (jogar/jogar-se pela janela), proveniente da mesma fenestra latina.

Já a palavra armazém no português é de origem árabe: al-makhzan, um lugar para guardar mercadorias, depósito; é daí que também surge a palavra portuguesa magazine[3].

Qual o objetivo de usar essas duas palavras? Elas servem para ilustrar como as línguas recorrem a termos de outras línguas e os incorporam, a ponto de nem serem mais identificadas como provenientes de outro idioma. Esse é um recurso muito normal, difícil de ser percebido em palavras mais antigas como armazém e bem mais fácil de ser identificado em palavras como sanduíche (obviamente proveniente do inglês sandwich). Algumas vezes, até mesmo alteramos o sentido de palavras quando empréstimos linguísticos são feitos: lunch (que em inglês significa “almoço”) vira lanche, que em português significa uma “refeição rápida ou pequena”.

Esse tipo de incorporação, porém, não permite que nós afirmemos que o português deixou de ser português porque agora usa as palavras armazém e lanche, ao invés de outras equivalentes que talvez já tenham caído em desuso ou quem sabe nunca tenham existido. Se assim fosse, seríamos privados de milhares de palavras; talvez só um punhado de palavras “genuínas”, o que quer que isto signifique, ficariam a nossa disposição.

O Caso do Hunsrückisch Brasileiro

O mesmo fenômeno ocorre com o Hunsrückisch brasileiro. Os alemães que imigraram para o Brasil nem sempre sabiam falar o alemão-padrão; em muitas áreas do novo mundo, o Hunsrückisch se estabeleceu como língua-padrão, por ter sido a língua da maioria (cf. Altenhofen 1996, Damke 1997 e Pupp Spinassé 2008). Ele funcionava como uma espécie de língua-franca, pois a origem de muitos imigrantes nem sequer era a região do Hunsrück, mas sim outras partes da área onde hoje estão situadas a Alemanha, a Áustria, a Suíça e até mesmo partes da França e da Polônia atuais, onde se falava alemão. Grande parte dessa imigração ocorreu de 1824 até o final daquele século. As comunidades se formavam e muitas vezes ficam isoladas, sem contato algum com a área de língua alemã dos antepassados, e algumas vezes até mesmo de certa forma isoladas em relação a outras áreas do próprio Brasil, onde se falava português, italiano e outras línguas.

As línguas são extremamente dinâmicas, apesar de muitas vezes nem nos darmos conta de que elas funcionam assim. Como exemplo anedótico, pensemos em uma pessoa dos anos de 1950, que tenha sido guardada em uma caixa naquela época e que só tenha sido libertada recentemente para ver o mundo dos nossos dias. Será que ela saberia do que estamos falando se citássemos termos como celular, computador, impressora, fibra ótica, crédito pré-pago, DVD, curtir e postar na rede social, entre outras centenas de verbetes e expressões? Certamente não, essa pessoa se sentiria completamente perdida, como se estivéssemos falando em outra língua ou “com códigos secretos”.

Algo parecido se deu com o Hunsrückisch brasileiro. Ele passou a existir de forma relativamente isolada em relação às variedades faladas na região do Hunsrück na Alemanha. Em compensação, porém, ele passou a conviver com as variantes do português brasileiro e, em algumas circunstâncias, também em contato com outras línguas europeias faladas no Brasil. Essa situação de contato é condição necessária para que haja um ambiente propício para a ocorrência de empréstimos linguísticos. Se nós já fazemos empréstimos de línguas com as quais sequer estamos em contato direto, então imaginemos a situação do Hunsrückisch no Brasil.

Além do desenvolvimento independente da língua de origem, com o passar do tempo, novas invenções surgiram e, com ela, a necessidade de criar ou emprestar centenas de palavras. Como “batizar” a televisão em Hunsrückisch brasileiro, se o termo do alemão-padrão não é conhecido e não está à disposição? Inevitavelmente a solução é recorrer à língua com a qual se está em contato, daí surge a solução e o nome do objeto, já adaptado à fonética do Hunsrückisch brasileiro: televisón. A outra solução é recorrer à criatividade e usar termos disponíveis na própria língua para criar a nova palavra: Bildakaschte (junção dos termos alemães “Bilder” e “Kasten”, significando em tradução direta para o português “caixa de imagens”), palavra que ocorre em algumas regiões e é uma variante de televisón. Nada de errado e nem de absurdo nisto, apenas um fenômeno linguístico passível de ocorrer em línguas vivas. Ou de onde os alemães teriam tirado a palavra Fernsehen (fern – longe, sehen – ver)? Ela é formada exatamente como televisão (do grego tele – longe, em junção com o latim visione – visão).

Em suma, quando um falante de Hunsrückisch brasileiro diz que o seu avô hot sich endlich aposentiert[4] (“finalmente se aposentou”), ele não comete nenhum erro, nenhum atentado absurdo à língua, nem demonstra que é pouco inteligente. Ao contrário, mostra como a língua é dinâmica, como ela pode se adaptar às necessidades e aos fatos do dia-a-dia. Ele demonstra, na verdade, que sua língua funciona perfeitamente como instrumento de comunicação, com regras gramaticais e fonéticas definidas, exatamente como qualquer outra língua. Inclusive, sequer foge à regra de ter exceções gramaticais. Com a expressão usada, esse falante exprime exatamente o que tem de ser dito para que a comunidade de falantes entenda o que pretende dizer. Ao contrário, se fosse arrogante e quisesse mostrar o quão é “versado”, dificilmente seria entendido pelos falantes do Hunsrückisch ao recorrer à expressão usada atualmente na Alemanha para dizer a mesma coisa: er ist in Rente gegangen ou er ist in den Ruhestand gegangen.

Conclusão

O preconceito em relação a este fantástico e completo sistema de comunicação que é o Hunsrückisch brasileiro, um verdadeiro tesouro que carrega dentro de si a cultura e a história de um povo, infelizmente ainda persiste. A falta de conhecimento em relação ao Hunsrückisch gera desconsideração. Uma pena que ainda haja alguns professores, inclusive de alemão, que ignorantemente desprezam o Hunsrückisch, procurando uma superioridade fantasiosa calcada em sua própria arrogância e ignorância acerca do funcionamento linguístico e orgânico de um sistema completo de comunicação oral, como é o caso do Hunsrückisch brasileiro.

O objetivo deste curto artigo foi demonstrar o quão importante é a reflexão e a compreensão adequada de fenômenos como o bilinguismo entre os descendentes de alemães, italianos, japoneses e de outras etnias, inclusive as indígenas, no Brasil. Não há justificativa científica para procurar eliminar o bilinguismo entre os falantes no Brasil, não há justificativa lógica nem prática para tal. Ser bilíngue é uma vantagem no mercado de trabalho no mundo todo, mas em nosso caso também é uma questão de não ignorar, apagar ou menosprezar a própria história. Somos o que somos, somos quem podemos ser.

Referências

ALTENHOFEN, Cléo Vilson. Hunsrückisch in Rio Grande do Sul. Ein Beitrag zur Beschreibung einer deutschbrasilianischen Dialektvarietät im Kontakt mit dem Portugiesischen. Stuttgart: Steiner, 1996.

BARANOW, Ulf Gregor. Studien zum deutsch-portugiesischen Sprachkontakt in Brasilien. Tese de Doutorado. München: Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität, 1973.

DAMKE, Ciro. Sprachgebrauch und Sprachkontakt in der deutschen Sprachinsel in Südbrasilien. Frankfurt am Main: Peter Lang, 1997.

PUPP SPINASSÉ, Karen. Os imigrantes alemães e seus descendentes no Brasil: a língua como fator identitário e inclusivo. Conexão Letras. Porto Alegre: PPG-Letras, UFRGS, 2008, vol. 3, n. 3, p. 125-140.

SCHAUMLOEFFEL, Marco Aurelio. Interferência do Português em um Dialeto Alemão Falado no Sul do Brasil. Bridgetown: Lulu, 2007.

SCHERRE, Maria M. P. Entrevista sobre Preconceito Linguístico, variação e ensino concedida a Jussara Abraçado. Caderno de Letras da UFF – Dossiê: Preconceito linguístico e cânone literário, n. 36, p. 11-26, 1. Sem., 2008.

WEINREICH, Uriel. Sprachen in Kontakt. München: Beck, 1976.

NOTAS

[1] Optou-se pelo termo Hunsrückisch brasileiro neste artigo para deixar claro que o autor se refere às variedades dele faladas no Brasil. Geralmente se diz que as variantes do alemão do Brasil são, predominantemente, originárias do Hunsrück. É importante, porém, frisar que não existe apenas uma variante naquela região (e nem no Brasil) que possa ser denominada assim. Há diversas variedades, embora com grande parte dos seus sistemas em comum. Desse modo, pode-se falar na Alemanha, por exemplo, de variedades como o Moselfränkisch e o Rheinfränkisch; este último, por sua vez, engloba variedades de Hessisch e Pfälzisch (Schaumloeffel 2007, p. 32-33). Para obter mais detalhes sobre o Hunsrückisch, recomendamos os estudos de Altenhofen (1996), Baranow (1973) e Damke (1997).

[2] Há muitos estudos sobre o fenômeno dos empréstimos linguísticos. Para maiores detalhes consulte p. ex. Weinreich (1976).

[3] Dicionários etimológicos são instrumentais para o estabelecimento da origem dos empréstimos linguísticos. Como os dois exemplos aqui citados são relativamente bem conhecidos, nenhum dicionário etimológico foi consultado. Porém, até mesmo uma consulta rápida on-line permite confirmar a sua origem. Para armazém veja http://www.dicionarioetimologico.com.br/ e para Fenster consulte http://www.duden.de/.

[4] Assim como muitas palavras, o verbo “sich aposentieren” (aposentar-se) apresenta diferentes variantes nas mais diversas regiões. Ele p. ex. também pode ser realizado como “sich aposehtere”, “sich aposentehren”, “sich aposentiere”. O sistema de aposentadoria só passou a existir em 1889 na Alemanha, portanto, provavelmente não beneficiava nem era conhecido pelos imigrantes alemães do Hunsrück no momento em que a maioria deles imigrou para o Brasil. O autor deste artigo é falante nativo da variedade Hunsrückisch falada em Boa Vista do Herval, localidade do município de Santa Maria do Herval – RS, e os exemplos citados aqui constam no corpus por ele coletado com mais de 13 horas de gravações feitas com 36 entrevistados selecionados de acordo com critérios sociolinguísticos (Schaumloeffel 2007).

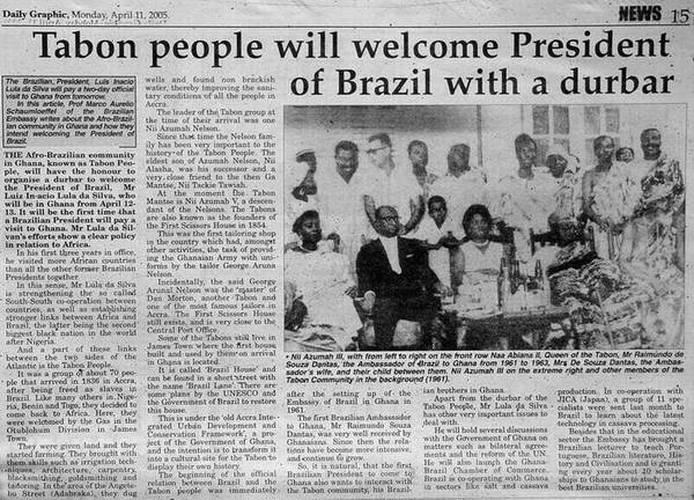

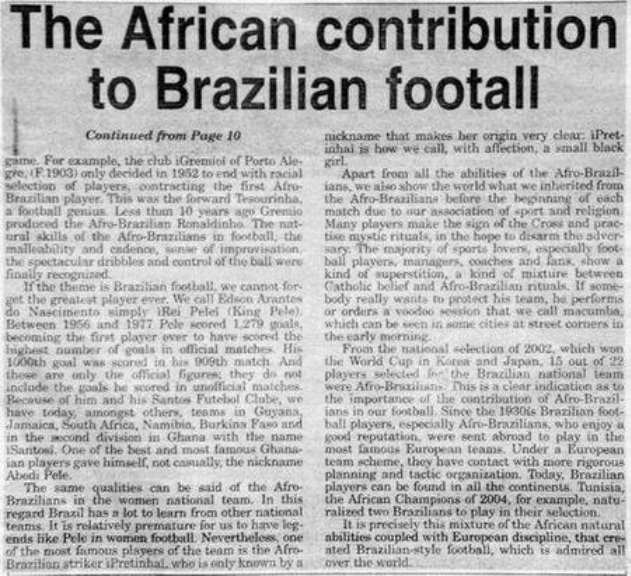

Entrevista concedida à revista Atlântico / Interview for Atlantico Magazine

Entrevista concedida à revista Atlântico / Interview for Atlantico Magazine