Considerations on the reciprocity and reflexivity in Papiamentu

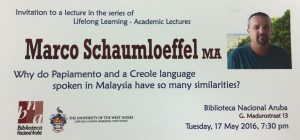

Marco Aurelio Schaumloeffel

Presentation at the 21st Biennial Conference of the The Society for Caribbean Linguistics (SCL)

Kingston, Jamaica 1st-6th August 2016

Conference Programme

Conference website

References

Abstract

Considerations on the reciprocity and reflexivity in Papiamentu

The Ibero-Romance clitic pronouns were not incorporated into Papiamentu (PA). Instead, PA has today several different possibilities to form reflexives, which replaced the Ibero-Romance clitics: paña ‘cloth’, kurpa ‘body’, null reflexive, possessive + kurpa, object pronoun, object pronoun + mes < Portuguese mesmo ‘self’, and possessive pronoun + mes (cf. Muysken 1993:286). At least two other strategies of reflexivisation or quasi-reflexivisation are not discussed by Muysken: the use of kabes ‘head’ and of the reciprocal otro ‘other’. While some of those types of reflexives are a common strategy of reflexivisation in several creole languages (Muysken and Smith 1994:271-288), some of them can also be found in other Portuguese-based creoles. Therefore, this might indicate that there is a linguistic link between PA and those creoles when it comes to the realisation of this category of function words.

The aim of this presentation is to ponder on how specifically the reflexives with kurpa, possessive + kurpa, kabes, otro and mes are realised in PA and compare them to their equivalents in other Portuguese and Spanish-based creoles in order to establish if there are linguistic ties that connect PA to them when it comes to reflexivity.

Reflexives with kurpa and possessive + kurpa are also found in the Guinea Bissau and Casamance Portuguese creoles (GBC), which in turn are usually correlated with a Kwa / Bantu substrate (Jacobs 2012:130-131), but are also present in Asian creoles like Papiá Kristang (PK) and Zamboangueño (Holm 2000:225). Reflexives or quasi-reflexives can also be formed with PA kabes, which also encounters equivalents in GBC, Cape Verdean Portuguese-based creoles and PK. Another shared feature of PA with GBC and PK is the use of ‘other’ to express reciprocity, whereas a similar syntax for PA mes can also be found in the Cape Verdean creole of São Vicente, in Principense and in PK.

Interestingly, the analysis of the available data always points towards the same direction, since the current realisation of reflexivity in PA seems to be etymologically, and sometimes even through its grammatical functions, linked to other Portuguese-based creoles and to Portuguese, rather than to Spanish or Spanish-based creoles. Holm raised two possibilities for the presence of a reflexive with ‘body’ in Asian creoles, which also can be extended to the other reflexives mentioned above: that they either spread by diffusion or arose independently through the influence of other substrate languages (2000:225). Based on their similar realisation, especially in PK, the former rather seems to be the case.